The Ultimate Guide to

Kanna

(Channa, Kougoed)

Kanna is a largely legal substance, though some extracts do require a prescription in certain countries. This guide is designed to enhance the safety of those who decide to work with kanna and should not be taken as medical advice. This blog article uses affiliate links. Third Wave receives a small percentage of the product price if you purchase through any affiliate links.

Overview

01An Introduction to Sceletium tortuosum

Sceletium tortuosum is a little-known psychoactive plant from South Africa. It has a variety of common names, including kanna, canna, canna-root, channa, gunna, kougoed, kauwgoed, Kauwgood, Kon (meaning “quid”), and Kou. Kougoed (and therefore “kanna” through association) means ‘chew(able) things’ or ‘something to chew’. Part of the confusion around the naming is that various different plants have been called “kanna”, “canna”, or “kouged”. Additionally, kanna shares its name with the eland antelope, the most revered animal in the cultures of the South African Bushmen and Hottentots, who are said to have named the plant after the antelope.

Kanna is a hardy, woody succulent with bright green fluid-filled leaves. The genus is named after the densely ‘skeletonized’ appearance of previous years’ leaves [1]. The plant is easily cultivated and has been popular with many ethnobotanical collectors worldwide who grow, ferment, and prepare their material for the plant.

While kanna is legal in all countries, it has received little attention outside of South Africa. Its main active constituents are mesembrine and mesembrenone. Although some writers have described it as a hallucinogen, kanna is only mildly psychoactive and often used with other plants, particularly cannabis or dagga (Lion’s Tail or Leonotis leonurus), but it is not considered a psychedelic.

Kanna is typically consumed by chewing but it can also be taken as a tea, smoked, or in capsules. Finely powdered material can also be snuffed, producing a calm euphoria or mood enhancement with clear thoughts, accompanied by a state of relaxed alertness and decreased anxiety. Kanna is regarded as an empathogenic plant—it opens up your heart, increases empathy, and helps you feel more connected.

The Botany of Kanna

Sceletium tortuosum (Linnaeus) N.E. Brown is in the family Aizoaceae (the ice plant family, Mesembryanthemaceae), sub-family Mesembryanthemoideae—otherwise known as the Mesembryanthemums. The kanna plant has also been known as Mesembryanthemum tortuosum (Linnaeus). This group of plants, the Aizoaceae, is known to be alkaloid rich, with several dozen species reported to contain alkaloids [2][3].

Sceletium tortuosum is a prostrate herbaceous shrub that grows up to 30 cm (12 in.) tall, and has fleshy roots and spreading branches of smooth, fleshy stems. The glossy green leaves are unequal, smooth, lanceolate-oblong, 4 cm (1½ in.) in length, and 1 cm (½ in.) wide. The thick, angular, fleshy leaves grow in groups of one to five; the white or pale yellow flowers are 4 to 5 cm (1 ½ -2 in.) wide. The leaves do not have stalks but are attached directly to the branches. The fruit is angular with small seeds.

Other species in the genus Sceletium include S. anatomicum, S. expansum, S. joubertii, S. namaquense, and S. strictum. Members of the genus Sceletium closely resemble each other and are easily confused with members of Mesembryanthemum. Species that resemble kanna, containing the same active constituent (mesembrine), having similar effects, and used in the same manner, are presumably referred to as kanna and kougoed [4][5][6]

The natural range of Sceletium tortuosum is South Africa. This and related species are perceived to be rare in South Africa [7]. The plant can be propagated through seeds or via cuttings. Seedlings are grown in the same way as cactus seeds; that is, scattered onto cactus or succulent soil and watered. The cultivation and care is similar to how you would care for succulents or Cactaceae.

The Confusion Around Kanna as a Common Name

Common names have caused many problems in identifying plants (or fungi) from historical sources. Soma is a prime example. It has been identified as either the fly agaric (Amanita muscaria), Syrian Rue, or Ephedra. Kanna (not the anime character!) suffers from the same lack of taxonomic detail in the historical records.

It is known that the Hottentots (Khoikhoi) of South Africa chewed several plants, which were known as channa, kanna, or kougoed—Sceletium tortuosum being one of these plants. Although kanna is primarily identified as Sceletium tortuosum, the common names are applied to several species of Sceletium known to contain alkaloids. Other plants suggested as kanna include Leonotis leonurus (otherwise known as dagga or lion’s tail), or Salsola dealata (known as Ganna) (Botsch). Louis Lewin, the german pharmacologist whose 1924 book “Phantastica” was one of the first to describe in detail many of the significant entheogens, was of the opinion that the plant may also have been Sclerocarya caffra or Sclerocarya schweinfurthiana [8].

Experience

02Preparing Kanna

The entire plant is known to contain alkaloids, but it must be prepared properly before it can be used. As is characteristic of the genera Sceletium and Mesembryanthemum, kanna is known to contain oxalic acid, which can produce severe irritation and allergies. To break down the oxalic acid, a process of fermentation is required.

Traditionally, the plant material is harvested in October, when the plant is most potent, then crushed between two rocks and allowed to “ferment” for a few days in a closed container. Animal skins or hemp bags were originally used for this purpose. The container is placed in the sun, then two or three days later the bag is opened, and the contents are mixed well. The bag is sealed and placed outside again. After a week, the kanna is taken from the bag and spread out to dry in the sun. When the plant material has dried, it is chopped or powdered and ready to be used.

Another method involves toasting fresh plant material over coals until it has completely dried and then powdering the result [7].

Products currently on the market consist of either the processed dried material, or a variety of extracts. Some shops or herbalists also stock various tinctures or elixirs that contain kanna or a combination of kanna and other plant medicines.

What is Kanna Extract?

Kanna alkaloids are mostly soluble in alcohol. By soaking the Sceletium tortuosum powder in food-grade ethanol or 99% isopropyl alcohol, the alkaloids can move from the plant material into the solution, saturating it with the alkaloids. After a period of time, the solution is filtered and the powder is squeezed well and discarded. The ethanol or isopropyl must then be fully evaporated out of the extract. Any residual alcohol can be toxic and unsafe to consume. Once the solution is completely washed, the result is a tar resin that is full of alkaloids. This extract can be mixed with kanna powder or other plant material. Alternatively, it can be kept as a resin.

What to expect

03EFFECTS OF KANNA

As one historic report recounted: “Their animal spirits became animated, their eyes sparkled, and their faces were marked by laughter and happiness. A thousand charming ideas arose in them, a gentle joy that amused itself over the simplest of jests.” [8]

As this description shows, traditionally kanna has been said to cause an excited intoxication, but the effects of small dosages of kanna are quite different. These can include relief from anxiety and stress, increase in self-confidence, a feeling of well-being, and a gentle decrease of inhibitions, thus allowing deeper social contact. Effects can also include euphoria and feelings of meditative tranquility. “Several users felt that the relaxation induced by kanna enabled one to focus on inner thoughts and feelings, if one wished, or to concentrate on the beauty of nature.” [7].Kanna can also increase sensitivity of skin and touch, and act as an aphrodisiac.

Higher dosages, especially when combined with Cannabis sativa, can produce mild visions.

Kanna has few reported adverse effects, with side effects known to include headaches, loss of appetite, and depression.

Pharmacology

04Mesembrine (empirical formula C17H23NO3) can be found in the leaves and stalks of the plant with 0.3% found in the roots and 0.86% in the leaves, stems, and flowers of the plant [7]. Mesembrine acts as a serotonin reuptake inhibitor with less prominent inhibitory effects on phosphodiesterase 4 (PDE4). In an in-vitro study, a high-mesembrine Sceletium extract showed monoamine releasing activity by up-regulation of vesicular monoamine transporter 2 (VMAT2) [11]. VMAT2 is a protein that transports neurotransmitters out of the cell, where they can have their effects. In the brain, VMAT2 transports—and thereby activates—molecules like dopamine, serotonin, and GABA.

Mesembrenone has been reported to serve as a more balanced serotonin reuptake inhibitor and also boosts energy use in the body by blocking an enzyme called phosphodiesterase 4, or PDE4.

Kanna is also reported to be an acetylcholinesterase inhibitor and cannabinoid agonist. In rats, active compounds of Sceletium tortuosum extract also activated the receptors for GABA, opioids, cholecystokinin, prostaglandins, and melatonin.

Toxicity

Many of the ice plants from the Aizoaceae are known to be high in oxalates (3.6-5.1% or more), including oxalic acid. Oxalates can be highly acidic and astringent, and can have toxic effects in large amounts; that’s why kanna should be fermented or heat-treated to degrade the oxalates [7] [12] [13].

Dosing

Kanna Powder

Powdered kanna is consumed orally and held in the mouth for about ten minutes. Saliva will collect in the mouth and this can be swallowed. For Sceletium tortuosum dosage, two grams produce a “tranquil mellowness” after 30 minutes, and five grams of the powder is sufficient to relieve anxiety, with higher dosages leading to more entheogenic effects (euphoria, visions) [7]. Doses from five grams up (equivalent to 150 mg mesembrine) can produce other effects such as mydriasis, analgesia, loss of appetite, tingling in mouth, gagging reflex, congested feeling in the head, and noises in the ears.

Kanna Extract

The dosage for Zembrin, a commercial Sceletium tortuosum extract from South Africa, is 25 – 50 mg per day for cognitive effects, with South African psychiatrists prescribing between 100 – 200 mg per day for major depression and anxiety. Researchers found that up to six mg per kg of body weight per day would be completely safe to consume [14]. For the average human adult, that means 420 mg per day, which is far above the effective dose

Microdosing

Microdosing involves using sub-perceptual doses of a compound, such as psilocybin or LSD, to elicit an ongoing benefit, such as enhanced levels of creativity, energy, and focus. The majority of microdosing regimes are based on using compounds that are similar in structure to the major neurotransmitters serotonin or dopamine, i.e. tryptamines or phenethylamines, respectively, which are 5-HT2A agonists. Kanna alkaloids are already potent and easy to set up a schedule with, especially if using gentle extracts such as “Play” from the Hearthstone Collective to bring yourself into the world of microdosing, and have plants and mushrooms work harmoniously with your body.

People are experimenting with microdosing various psychoactive compounds. If you are curious about how to microdose with kanna and want to learn how to start microdosing using a science-based, step-by-step process, Third Wave’s new and improved Microdosing Course can show you how. The course will guide you through the basics—then dive much deeper, helping you tailor your routine to meet your personal goals. The course does not explicitly teach you how to use kanna, but can help create a strategy to incorporate it into your life for optimal benefits.

Other Methods

Other methods include making a tea of the dried herb, snuffing very finely ground powder, either alone or with tobacco, or smoking the powdered kanna alone or combined with Cannabis sativa, or Lion’s Tail. Often, plant material may be too coarse for snuffing so it is best to powder the prepared herb in a general purpose spice grinder, then snuffing the very fine powder that collects on the inside of the lid. As little as 20-30 mg may be required for snuffing.

Kanna can also be added to beer for a psychoactive effect, or to induce fermentation [7]. Chewing kanna after smoking cannabis can potentiate the effects. Kanna is said to suppress both the effects of tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum) and the desire for nicotine.

Benefits & Risks

05

Potential Benefits

Kanna (Sceletium tortuosum) benefits include:

- Improved mood, stress relief, and boosted feelings of happiness, well-being, and wellness

- Improved focus and cognition

- Decreased pain

- Decreased hunger

Kanna is also known to assist in overcoming addiction.

The natives of Namaqualand and Queenstown (southern Africa) drink a tea made from the

leaves that acts as an analgesic and suppress hunger [7].

Risks

A small and minor risk is oxalic acid, but for properly fermented kanna this should not be a problem. It is advised to not consume fresh or only partially fermented kanna.

As kanna is a serotonin reuptake inhibitor, it may interact dangerously with many other substances, including but not limited to: Warfarin, antipsychotics, Sibutramine, Tramadol, and St. John’s Wort. Caution should be used in individuals taking psychoactive drugs such as anxiolytics, sedatives, hypnotics, or antidepressants.

Apply caution when combining medications. We recommend you talk to a doctor to avoid adverse effects and unexpected interactions.

Because kanna is a serotonin reuptake inhibitor, it should also not be used with other SSRIs (serotonin reuptake inhibitors). Too much serotonin in the nervous system can cause a condition called serotonin syndrome. In minor cases, people who experience serotonin syndrome will report symptoms such as tremors, twitching, anxiety, insomnia, and increased heart rate. If serotonin levels get high enough, serotonin syndrome can cause seizures, delirium, and extremely high body temperature. In extreme cases, a person suffering from serotonin syndrome can fall into a coma. The symptoms of serotonin syndrome vary from person to person, and they range from mild to life threatening

Therapeutic use

06A Sceletium tortuosum extract rich in mesembrine has been shown to decrease the stress hormone, cortisol. Researchers suggested that the extract may be useful in people with high stress and high blood pressure [15] [16]; these results have yet to be verified in animal or human studies.

Legality

07Legality: Is Kanna Legal?

Sceletium tortuosum in all its forms (as dried herbal material, extract, and tincture) is legal in all countries when sold as an herbal preparation. It is sold openly in many herbal stores and shops. In many countries, there are regulations around making claims of any herbal medicine (FDA in the United States, TGA is Australia), so like many other beneficial herbs, it is sold as a purely herbal product based on its traditional use.

In South Africa, a kanna extract is sold as Zembrin, which is only available by prescription.

Sourcing

Given its legal status, there are no restrictions on kanna, except when it comes to making claims for it as a healthcare or pharmaceutical product. Therefore, finding kanna and kanna-based products is relatively easy. As with many products, the only difficulty can be confirming how the plant material was sourced, and whether it was ethical, especially within a globalized economic system dependent upon labor from developing nations.

Kanna and kanna extracts can sometimes be obtained from herbal stores, but keep in mind that some plant products can quickly appear and then disappear. Kanna extracts can be sold at various potencies, up to 100x, and have a strong, almost bitter tobacco flavor. Kanna can also be sold as tinctures or in combination with other plant medicines.

Third Wave recommends the kanna extract “Play” from the Hearthstone Collective. “Play” contains kanna, lion’s mane, rhodiola, theobromine, and B-complex vitamins for an outgoing, energizing, and stimulating experience. “Relax” is for anxiety, calming the mind and for grounding. The Hearthstone Collective works with ethically sourced plant (and fungi) material from plants with high levels of alkaloids. They produce a high-quality product to help you reconnect with your body and nature, to build community around powerful medicines, and to help restore the ecology of our beautiful earth.

Seeds of Sceletium tortuosum and other Sceletium species, sometimes under the synonym

Mesembryanthemums, are occasionally available through specialist nurseries and ethnobotanical sources. Cactus and plant enthusiasts sometimes offer living specimens of the genus, and they can sometimes be found through plant swaps or giveaways.

Ethical Considerations

08To minimize any threats to wild populations, plant material in the form of dried herb, extracts, seeds, or cuttings should not be sourced from wild populations of the plant, but from cultivated populations. Fortunately Sceletium tortuosum is easy to cultivate, and it is known that other Sceletium species contain similar alkaloids.

Sceletium tortuosum is not known to be weedy or invasive, but care should be taken with any plant when introducing it to an area where it is not known. Many plants, though seemingly innocent looking, can escape and cause significant ecological problems.

History & Stats

09extremely visionary, was inspired by the use of kanna [18] . Kanna was first recorded during the 1600s by Dutch explorers in South Africa. Although we now regard Sceletium tortuosum as kanna, some mystery surrounds its background. It is thought that the plant was used in South Africa as a mood-altering substance by hunter-gatherers from prehistoric times.

The first report of kanna was from Peter Floris, who mentions the plant in his Voyage To The East Indies In The Globe 1611—1615. In Floris’s account, kanna appears similar to Korean ginseng in having “an extraordinary reputation in China as a restorative.” However, he was unsuccessful in obtaining any fresh material. Jan van Riebeeck wrote the first-known written account of the plant’s use in 1662. Van Riebeeck traded with indigenous tribes in southern Africa, exchanging sheep for kanna, which was once again identified as a ginseng-like herb.

The Hottentots (Khoikhoi) and other South African groups (e.g., the Namaquaa) were reported by botanist and astronomer Peter Kolbe as consuming plants known as kanna, Canna, or Channa, which were chewed for their rituals, healing dances, and as a vision-inducing hallucinogen [19]. Unfortunately, most explorers neglected to provide any information about the botanical source. It was not until the end of the nineteenth century that it was suggested that the plant must have come from Mesembryanthemum spp., for these species were then still known by the name kanna in South Africa. Kanna had become associated with Sceletium expansum, Sceletium tortuosum, Sceletium anatomicum, and Carpobrotus edulis. There is no evidence specifically connecting past or modern Mesembryanthemum use with the Hottentots.

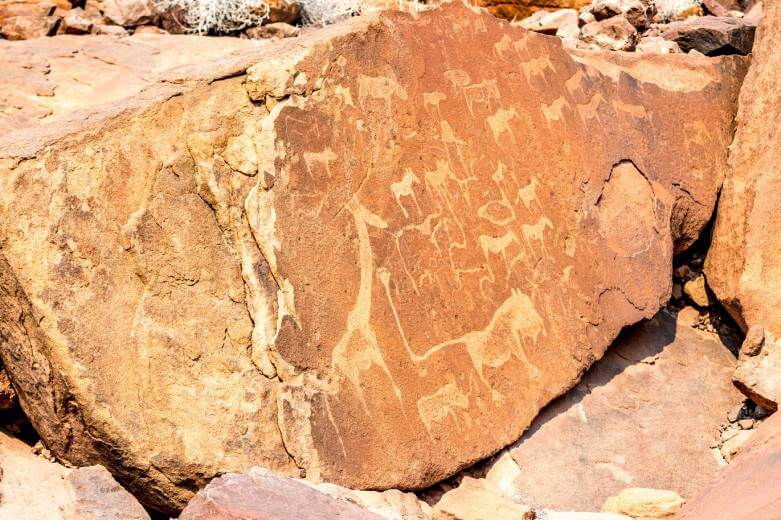

The South African Bushmen (San) use the same name for Sceletium tortuosum as they do

for the eland antelope (Taurotragus oryx): kanna. The Hottentots (Khoikhoi) also use the name kanna for the magical eland antelope [7]. The Bushmen have regarded the eland as the “trance animal” par excellence since prehistoric times, playing a central role as a magical ally in ceremonies, closely associated with rain-making and divination, healing, and communal trance dances [18]. Kanna is also used as part of rituals. The San and the Hottentots (Khoikhoi) would travel long distances by foot, and would chew on fermented kanna to relieve their thirst and discomfort.

In his 1924 book, Phantastica, researcher Lewis Lewin doubted whether plants from the family Aizoaceous could be responsible for the effects described. He suggested that the narcotic might have been Cannabis sativa, which the Hottentots do use habitually. He further pointed out that other intoxicating plants in South Africa, such as Sclerocarya caffra and S. schweinfurthiana, should be considered candidates.

MYTHS

10FAQ

11Can you die from taking kanna?

Care should be taken with kanna, as it is a serotonin reuptake inhibitor. Accordingly, it should not be used with other serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Too much serotonin in the nervous system can cause a condition called serotonin syndrome. In extreme cases, a person suffering from serotonin syndrome can fall into a coma. The symptoms of serotonin syndrome vary from person to person, and they range from mild to life threatening.

Is kanna easy to grow?

Kanna is very easy to grow. It can be grown from seed, or it can be grown from cuttings. Seeds are germinated in the same way as cacti, either finely spread on a surface of cactus soil or using the takeaway tek. Sceletium tortuosum grows in arid, sandy soils, with occasional watering.

Is kanna caffeine-free?

The plant material of kanna contains no caffeine.

How much kanna extract should I take?

This is dependent on how your kanna extract is made. The dosage of a 10x extract would be 2.0g, and a 100x extract would be 0.2g. The exact amount is likely to vary depending on manufacturer, so check the description on the product for the recommended dosage.

References

12[1] Gerbaulet, M., (1996). Revision of the genus Sceletium N.E. Br. (Aizoaceae). Botanische

Jahrbücher 118, 9–24.

[2] Schultes, R.E. (1976). Indole Alkaloids in Plant Hallucinogens. Planta Medica 29, 330~342.

[3] Arndt, R. R., and Kruger, P. E. J., (1970). Alkaloids from Sceletium joubertii L. Bolus: the structure of joubertiamine, dihydrojoubertiamine and dehydrojoubertiamine. Tetrahedron Letters 37:3237–40.

[4] Jeffs, P. W., G. Allmann, H. F. Campbell, D. S. Farrier, G. Ganguli, and R. L. Hawks. 1970. Alkaloids of Sceletium species III: The structures of four new alkaloids from Sceletium strictum. Journal of Organic Chemistry 35:3512–28.

[5] Jeffs, P. W., T. Cappas, D. B. Johnson, J. M. Karle, N. H. Martin, and B. Rauckman. 1974. Sceletium alkaloid VI: Minor alkaloids from Sceletium namaquense and Sceletium strictum. Journal of Organic Chemistry 39:2703–9

[6] McKenna, D.J., Towers, G.H.N. and Abbott, F. (1984) Monoarnine oxidase inhibitors in South American hallucinogenic plants: tryptarnines and 0-carboline constituents of ayahuasca. Journal of Ethnopharmacology 10, 195-223.

[7] Smith, Michael T., Neil R. Crouch, Nigel Gericke, and Manton Hirst. 1996. Psychoactive constituents of the genus Sceletium N.E. Br. and other Mesembryanthemaceae: A review. Journal of Ethnopharmacology 50:119–30. http://www.sceletium.org/sceletium-review-article.html

[8] Lewin L. Phantastica. Die betäubenden und erregenden Genussmittel. Für Ärzte und Nichtärzte. Berlin: Verlag von Georg Stilke, 1924.

[9] Popelak, A. and Lettenbauer, G. (1968) The mesembrine alkaloids. In: R.H.F. Manske (Ed.), The Alkaloids. Vol. 9. Academic Press, New York, pp. 467-482.

[10] Frohne, D., & Jensen, U. (1979). Systematik des Pflanzenreichs unter besonderer Berücksichtigung chemischer Merkmale und pflanzlicher Drogen. Fischer.

[11] Coetzee, Dirk & Lopez, Victor & Smith, Carine. (2015). High-mesembrine Sceletium extract (Trimesemine™) is a monoamine releasing agent, rather than only a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 177. 10.1016/j.jep.2015.11.034.

[12] Steyn, D.G. (1934). The Toxicology of Plants in South Africa (Together With a Consideration of Poisonous Foodstuffs and Fungi). Central News Agency Ltd., London.

[13] Watt, J.M. and Breyer-Brandwijk, M.G. (1962) The Medicinal and Poisonous Plants of Southern and Eastern Africa 2nd ed. Livingstone, London.

[14] Murbach, T. S., Hirka, G., Szakonyiné, I. P., Gericke, N., & Endres, J. R. (2014). A toxicological safety assessment of a standardized extract of Sceletium tortuosum (Zembrin®) in rats. Food and chemical toxicology : an international journal published for the British Industrial Biological Research Association, 74, 190–199. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fct.2014.09.017

[15] Terburg, D., Syal, S., Rosenberger, L. A., Heany, S., Phillips, N., Gericke, N., Stein, D. J., & van Honk, J. (2013). Acute effects of Sceletium tortuosum (Zembrin), a dual 5-HT reuptake and PDE4 inhibitor, in the human amygdala and its connection to the hypothalamus. Neuropsychopharmacology : official publication of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology, 38(13), 2708–2716. https://doi.org/10.1038/npp.2013.183

[16] Manganyi, M. C., Bezuidenhout, C. C., Regnier, T., & Ateba, C. N. (2021). A Chewable Cure “Kanna”: Biological and Pharmaceutical Properties of Sceletium tortuosum. Molecules (Basel, Switzerland), 26(9), 2557. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules26092557

[17] Victor, J.E. & Powell, E. 2005. Sceletium tortuosum (L.) N.E.Br. National Assessment: Red List of South African Plants version 2020.1. Accessed on 2022/05/05 http://redlist.sanbi.org/species.php?species=100-22

[18] Lewis-Williams, I. D. 1981. Believing and seeing: Symbolic meanings in southern San rock paintings. London: Academic Press.

[19] Kolbe, Peter. (1978). ‘Naauwkeurige beschryving van de Kaap de Goede Hoop’