Disclaimer: Psilocybin is a largely illegal substance, and we do not encourage or condone its use where it is against the law. However, we accept that illicit drug use occurs and believe that offering responsible harm reduction information is imperative to keeping people safe. For that reason, this document is designed to enhance the safety of those who decide to use these substances. You can learn more about the legality of Psilocybin cubensis mushrooms here.

Remember the advertisements depicting fried eggs as “Your brain on drugs?” Those campaigns were creative. But they weren’t exactly true, especially for magic mushrooms.

In the video above, Third Wave Founder Paul F. Austin describes what really happens to your neural networks on high doses of psilocybin mushrooms.

Here we reveal what science knows and still can’t explain about your brain on shrooms.

What happens to the brain when you ingest psychedelic mushrooms?

Many of magic mushrooms’ neural mechanisms are still uncharted. But research indicates psilocybin is the primary psychoactive compound responsible for their psychedelic effects.

Psilocybin breaks down to the bioavailable compound psilocin in the body. Psilocin binds to serotonin, dopamine, and adrenergic receptors, affecting mood, visual input, emotional processing, and perception. Psilocin also reduces blood flow to the amygdala, the brain’s fear and anxiety center, while reorganizing communication networks and forging previously non-existent connections.

Neuroplasticity, mushrooms’ ability to grow novel neural links and enhance brain flexibility by binding to neural receptors, is one of their greatest healing powers. Mind-manifesting hallucinations are also critical to their profound mental benefits.

The neuroscience behind psilocybin mushrooms

Psilocybin’s action is complex, binding with multiple neurotransmitter receptors throughout the brain. Still, research shows psilocybin has a particular affinity for serotonin receptors. It mainly activates brain regions with high levels 5HT2A but also interacts with regions containing 5HT2C receptors.

Psilocybin and serotonin receptors

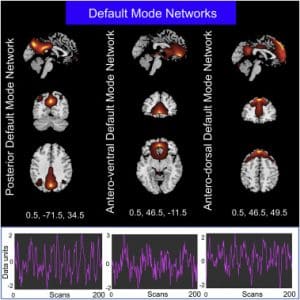

5HT1A and 5TH2A serotonin receptors gather in various neural networks, such as BA19 and BA37, involved in language and visual perception. These serotonin receptors also gather densely in the brain’s default mode network (DMN), including the anterior medial prefrontal cortex and posterior cingulate cortex, which is responsible for remembering, future thinking, and mind wandering.

Brain regions involved in verbal processing and emotions, such as the supramarginal gyrus and temporal cortex, and executive control regions, like the dorsal anterior cingulate cortex (dACC) and dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, also include high receptor levels.

By binding to 5HT1A and 5TH2A throughout the brain, psilocybin creates novel patterns that affect:

- Visual input

- Memory

- Body sensations

- Higher cognition

- Planning, goal-seeking, learning

- Instinct and body regulation

- Blood flow

What creates the hallucinogenic effect from psilocybin mushrooms?

Photo credit: Wired UK

Hallucinations are trademark effects of traditional psychedelics, like magic mushrooms, ayahuasca, DMT, and LSD. But neuroscientists are still exploring why they occur.

Imperial College London research, led by Dr. Robin Carhart-Harris and Professor David Nutt, discovered that psilocybin, a serotonin receptor agonist, linked parts of the brain that previously had no communication. By comparing fMRI brain scans of people who had ingested psilocybin to those on a placebo, the Imperial team discovered psilocybin decreased activity in advanced evolutionary brain regions and triggered action in other areas not typically online during normal states of consciousness. For example, psilocybin activates primitive brain networks linked to emotions and memory, including the hippocampus and anterior cingulate cortex.

Researchers observed that the human brain functioned with fewer rules and more engagement in the hallucinogenic state, similar to what happens during dreaming. The team also theorized that greater communication across brain networks could explain the synaesthesia that sometimes occurs during psychedelic experiences. Synaesthesia is an enigmatic sensory phenomenon where people taste colors, see smells, and feel sounds.

Imperial College London’s landmark research ignited a critical conversation about how psychedelics create altered states of consciousness. However, the scans failed to pinpoint the mechanism behind the visual hallucinations themselves. Recent research sheds more light on the topic.

A meta-analysis of the effects of tryptamine psychedelics on the brain shows that substances like psilocybin activate visual brain areas, primarily BA19 and BA37. These regions are packed with psilocybin’s favorite serotonin receptor, 5-HT2A.

Additionally, psychedelics disrupt information processing in inhibitory cortico-striato-thalamocortical (CSTC) feedback loops associated with filtering internal and external information to the cortex. Scientists theorize this disruption could lead to mental processing overload and hallucination formation.

Psilocybin also recruits higher-level brain regions, like the prefrontal cortex and temporal areas, to create structured, personal, and meaningful visions that lead to profound transformations.

Psilocybin and the default mode network (DMN)

Photo credit: Neuro Image Journal

The DMN is a powerful neural network that forms the basis of self-identity. In normal states of consciousness during periods of rest, the default mode network ramps up, leading to internal chatter, mind wandering, future worrying, and self-obsessive thoughts.

People with highly active default mode networks are typically more anxious and depressed, because they’re constantly ruminating on past trauma and mistakes, future fears, and internal criticisms. The same people are also more likely to seek solace in dangerous, addictive substances and harmful behaviors like eating disorders.

Psilocybin’s incredible power comes from its ability to change DMN wiring. Research indicates this classic psychedelic compound decreases connectivity within key components of the DMN, creating novel connections that support sensory and high-level emotional and cognitive processes.

In other words, psilocybin gives people a break from the obsessive thoughts that have defined their sense of self, allowing them to relive repressed memories without the stories attached. And, in that DMN reprieve, with high-level emotional and cognitive regions online, people can reframe trauma from an insurmountable tragedy into a healing opportunity.

Psilocybin and the amygdala

While magic mushrooms’ DMN-rewiring is essential, emerging research shows the amygdala also plays a crucial role in transformative experiences.

The amygdala is the brain’s center for emotions, emotional behavior, and motivation. It serves an essential evolutionary purpose, helping people detect danger and respond accordingly. But some people have overactive amygdalas when there’s no imminent threat, causing unnecessary aggression and fear.

For example, people with PTSD continue living in fear of traumatic memories that no longer exist in the present, because the amygdala still senses danger. Chronic amygdala overstimulation ultimately makes PTSD, depression, and anxiety symptoms more severe. It can also condition fear in otherwise healthy individuals.

Psilocybin’s therapeutic power lies in its ability to deactivate part of the amygdala by reducing blood flow to the region. This action weakens people’s reactions to triggering stimuli, reducing the emotional intensity that’s trapped them in the past. Free from the fear associated with trauma and conditioning, people can harness psilocybin hallucinations to emotionally process challenging memories for the first time in their lives.

Johns Hopkins University research on healthy subjects showed that psilocybin-induced diminished amygdala response endured one week after the psychedelic experience, eventually returning to baseline one month later. The Johns Hopkins team theorized they could extend this window by providing professional therapeutic support.

In 2022, Johns Hopkins Medicine researchers conducted a follow-up study on some of the same patients. This time they found psilocybin, combined with a supportive psychotherapy container, allowed treatment-resistant depression symptoms to subside for at least a year after their second dose.

Microdosing and the brain

Most psilocybin brain-imaging studies focus on magic mushroom effects at high doses. However, scientists are starting to expand research to psilocybin microdosing as well.

Microdosing, taking sub-perceptual or sub-threshold psychedelics doses, is an increasingly popular practice. People microdose psilocybin and LSD regularly for mood elevation, anxiety reduction, and cognitive enhancement. Many also tout the practice for its antidepressant benefits, as shown in Paul Stamets’s observational psilocybin microdosing study.

In 2020, the Beckley Foundation conducted a placebo-controlled within-subject study investigating the effect of a single low dose of LSD on BDNF (brain-derived neurotrophic factor) levels in healthy volunteers. BDNF is an essential protein that scientists associate with improved mental health, learning, and memory.

Beckley’s blood-sample findings indicated that LSD microdosing caused a dose-proportionate rise in BDNF six hours after administration. The study focused on LSD, not psilocybin. But LSD and psilocybin’s similar neural mechanisms indicate a psilocybin microdosing trial might produce similar results.

Also, the world’s first study protocol for a randomized, double-masked, placebo-controlled trial of microdosing in healthy volunteers confirmed that the practice improves self-reported ratings of connectedness, creativity, happiness, and energy. The study, from the University of Auckland, hasn’t published its complete findings yet. But the research team believes fMRI imaging will reveal greater levels of neuroplasticity and changes in the DMN than with a placebo.

Clinical trials and research on psilocybin for mental health

Psilocybin’s neuroplasticity has far-reaching implications for depression, PTSD, end-of-life anxiety, and addiction.

Mental health care company COMPASS Pathways is the farthest along in providing clinical proof. COMPASS recently published a phase IIb clinical trial on psilocybin therapy, adding double-blind evidence to the growing body of psychedelic research. In the largest randomized, placebo-controlled study worldwide, COMPASS showed that a single 25 mg dose, merged with psychotherapy, led to a statistically significant improvement in depressive symptoms after three weeks, with a “rapid and durable response for up to 12 weeks.”

Psilocybin’s proven efficacy for treatment-resistant depression explains why most experts believe this psychedelic compound will be the second, behind MDMA, to receive FDA approval in the next two years.

In addition to treatment-resistant depression, psilocybin research and clinical trials are underway for:

- End-of-life anxiety

- Alcoholism

- Trauma-related disorders

- Eating disorders

- Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD)

Side effects

Psilocybin is a powerful therapeutic tool and the safest drug to consume, according to an independent scientific committee. But psilocybin is not a guaranteed solution to suffering nor a passive medication. People who choose to sit with high-dose psilocybin for mental health purposes must seek a supportive, professional container to avoid potential side effects, such as a “bad trip.”

Bad trips can occur when overwhelming material comes up during a psilocybin journey, and people don’t have the emotional bandwidth to process it alone. Psilocybin-induced visions and sensations can be unsettling experiences that trigger trauma and reinforce the negative patterns people hope to overcome. People who take psychedelics are also more likely to experience psychosis-like symptoms, meaning not everyone is a candidate to take them.

Fortunately, medical professionals can mitigate these risks by screening patients and preparing them for the experience. Third Wave’s psychedelics directory highlights trusted providers that can help people responsibly access psilocybin and other expansive medicines.

Your brain on psilocybin mushrooms: final thoughts

Brain-imaging studies show that psilocybin mushrooms profoundly affect neural circuitry, making it much less restrained than during normal conscious states. The brain’s fear center and default mode network can finally take a break, while higher-level learning, emotional processing, and visual input reveal a new sense of self–a self untethered from trauma and conditioning, and free to begin the healing process.

Professional psychedelic support is essential for people with past trauma or mental health concerns. If you’d like to journey with psilocybin for therapeutic purposes, consider one of the psychedelic retreats, clinics, or practitioners in Third Wave’s psychedelic directory. The Third Wave team has verified or rigorously vetted all providers, including in-depth personal reviews. You can feel confident knowing these organizations are worth considering for vulnerable, transformative experiences.